Analysis of 仁 and Katō Jōken’s methodology

I. Analysis of 仁

— Conclusion

II. Katō Jōken’s methodology

— Conclusion

III. Notes

IV. References

Schuessler finds early meanings for the word¹ 仁 in the Shījīng (ca. 1050-600 BCE) and Shūjīing (a collection of texts from various periods, ranging 1050-206 BCE) “be kind, good”, and in the Lùnyǔ (475-221 BCE) and Mèngzǐ (340-250 BCE) “kind, gentle, humane”.

Even in reconstructions of Old Chinese the pronunciation of “be kind, good” 仁 and “person” 人 are simply identical. Yet Schuessler writes that while 人 “may possibly be the same etymon as ... 仁” he thinks it’s “[m]ore likely” that the two words have different origins.²

How did the ancients think about that?

The classic book Zhōngyōng 中庸 “The Doctrine of the Mean” seems to have been written as early as “the third century BCE” or as late as “either the Qin Dynasty era (221-208 BCE ), the initial decades of the Han Dynasty, following its founding in 202 BCE , or the time of chaos in between”.³

The Zhōngyōng says: 仁者,人也。⁴ Robert Eno translates this as: “‘Humanity’ means ‘human’”.⁵ In a marginal note Eno comments: ““Humanity” (ren 仁) and “human” (ren 人) were cognate words [in] Mencian thought”.⁶

Schuessler notes that the older variant ways of writing the word 仁 (either with the graph 忎 or with a form that uses 身 instead of 千 above 心) “suggest that its association with ... 人 ‘human being’ is relatively late” (citing Pulleyblank and Baxter). He goes on to state that “later it acquired the usual interpretation as lit. ‘act like a human being’”.⁷ Some scholars show an oracle bone variant that already combined 人 with 二, but this identification may be controversial.⁸ Contemporaneous variants also show combinations of 二 with other human shapes than 亻/人 (like 尸).⁹

Schuessler may be entirely correct in his assessment of how the meaning of the word 仁 developed, but both 心 and 人 appear to be valid semantic elements for its early meanings. Ochiai, working from meanings for the word 仁 like “to be intimate with; to befriend; to feel for; to be considerate of”, writes that either using 人 or 心 as a siginfic (意符, the part of a Chinese character that hints at its meaning) readily establishes the meaning of 仁. He adds that the component 千 in 忎 is phonetically close to 人. Ochiai further argues that 人 may serve both semantic and phonetic functions, while the component 二 (“two”) is unlikely to act as a phonetic element, since reconstructions show it lacks the final consonant found in 仁. Instead, he notes that “in ancient excavated script materials 二 is used as a duplication symbol”, which would account for its semantic role.¹⁰

Most scholars classify 仁 as a semantic compound in which the element “person; people; human” 亻/人 also contributes phonetically, a type known as 會意兼形聲 (lit. “semantic-phonetic compound with associative elements”).¹¹ Ochiai agrees.¹²

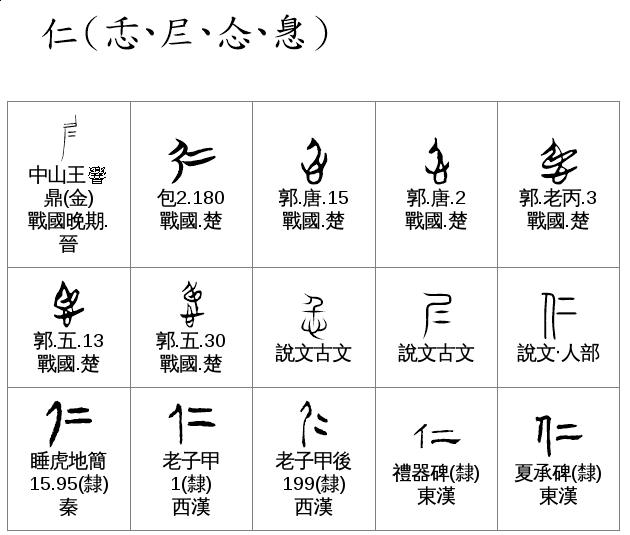

However, as noted above, variant forms of the character 仁 existed from the earliest stages. See the overview from the Xiaoxuetang Database below, and note the standardized versions of some of these variants shown at the top.

Some late-20th-century Japanese scholars argued that, in the character 仁, the component “two” 二 serves as a “phonetic with associated sense”. ¹³ In this view, 二 both signals the pronunciation of 仁 and hints at an additional lexical meaning. Katō Jōken further maintained that such phonetic components often point back to the original word for which the graph was devised.¹⁴

Below, I take a closer look at Katō’s analysis of 仁. As mentioned earlier, Ochiai rejects the idea of 二 as a phonetic component, since it lacks the final consonant present in 仁.¹⁵ He adds that “since 人 is already a phonetic loan with the same sound, it is unexpected that a character with a more distant pronunciation would have been used as a phonetic component on top of that.”¹⁶

Conclusion

It’s unclear whether the words 人 and 仁 derive from the same source, but by around 200 BCE, people seem to have perceived them as related. Since the two were pronounced identically at the time, it’s likely that the notion of 仁 was largely confined to scholarly circles or the written language.¹⁷ During the Eastern Zhou period (770–221 BCE), scribes used several different forms to write 仁 (see the table above), but eventually standardized the character as 仁.

Most scholars interpret 仁 as a semantic compound in which “person; people; human” 亻/人 and “two” 二 together express the intended word, with 亻/人 also contributing phonetically. According to Schuessler, the word 仁 originally carried meanings such as “be kind, good,” “to love,” and “kind, gentle, humane”. At some point, scholars appear to have regarded 仁 as, in effect, an elaboration or idealization of “being human”.

Katō Jōken’s methodology

Ever since I used Kenneth G. Henshall’s book A Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters, which draws heavily on work done by Katō Jōken and his student Yamada Katsumi, I’ve been curious about Katō’s methodology. In the introduction to his book Kanji no kigen, Katō uses the character 仁 to illustrate his approach. I’d therefore like to take a closer look at that example.

Somewhat surprisingly, Katō begins by claiming to have identified a very old form of 仁 that lacks the element 二 and instead shows a different human-like shape. He apparently bases this identification on the entry 儿 in Xǔ Shèn’s famous dictionary of graphical etymology of Chinese characters Shuōwén Jiězì (published in the beginning of the second century).

However, the graph Katō prints in his book (![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[img of seal script version of 儿]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/%E5%84%BF-513f-seal-script-version-from-%E8%AA%AA%E6%96%87%E8%A7%A3%E5%AD%97.svg)

![[img of seal script version of 儿 Duanzhu rendering ]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/%E5%84%BF-513f-seal-script-version-from-%E6%AE%B5%E6%B3%A8-for-%E8%AA%AA%E6%96%87%E8%A7%A3%E5%AD%97.png.svg) .¹⁸

.¹⁸

Let’s begin by examining what Xǔ Shèn says about 儿. He glosses the graph using 仁 as an adjective: 仁人也。古文奇字人也。象形。 “儿 is a good person. In ancient script, it is a variant form of the character for person (人). It is a pictogram.”

Xǔ Shèn goes on to cite a quote he attributes to Kǒngzǐ 孔子 [Confucius]: 在人下,故詰屈[詘]. A modern Chinese translation renders this as: 儿在字的下部,所以形体弯曲¹⁹—“(The component) 儿 is in the lower part of the character, therefore its form is bent”.

It’s unclear to me why Xǔ Shèn glosses 儿 as a “good, humane” human being, given that he himself clarifies that 儿 is a variant of “human being” 人 that is used as the bottom component in many characters. Perhaps he thought that as an independent graph it had an independent special meaning? At least Katō seems to think so.²⁰

As for the quote attributed to Kǒngzǐ (it may not actually be his), Tāng Kějìng’s modern Chinese translation explains that 儿 is a curved or compressed form of 人, as it typically appears beneath the main part of a character, where space is limited. This can be seen in characters like 先, 兒, and many others.

I suspect Katō was drawn to this entry in Xǔ Shèn’s work precisely because of the gloss stating (儿)仁人也. However, he ultimately rejects Xǔ Shèn’s explanation and disregards the accompanying quote. Instead, he offers a unique interpretation of the graph 儿 as a “kneeling figure”—more specifically, “a hunch-backed bearer carrying a burden on his back,” even though no burden is depicted.²¹ He bases this reading on the following entry in the Shì Míng:

仁,忍也。好生惡殺,善含忍也。²² “rén [goodness, kindness, love, humanity] is endurance. It cherishes life and detests killing. It is characterized by the ability to harbor forbearance.”²³

This is what Katō has to say about the Shì Míng:

Although this book has not been highly regarded by some scholars, others have praised its intent. In my view, many of its explanations—based on identical or similar sounds, are quite farfetched, yet there are also parts where the book is able to explain the etymology accurately, making it a fascinating work.²⁴

Katō himself acknowledges that many of the Shì Míng’s explanations “are quite far-fetched.” This helps explain why many scholars regard the text as unreliable. In my view, its entries can serve only as starting points for more substantive research. However, in this instance, it appears that Katō’s analysis relied solely on a comparison between Xǔ Shèn and the Shì Míng.

Returning to 仁, Katō asserts that ![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

In the Shuōwén, “儿” (

) is interpreted as “a good, humane person” (仁人), but this is really (これこそ) “a hunchbacked person” (背虫人).

Katō appears to base his conviction on another graph, ![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen. p. 7, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p7-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen. p. 7, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p7-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

In his introduction Katō concludes his segment on 仁 with:

The kneeling figure depicts a hunch-backed bearer carrying a burden on his back. From the idea of shouldering that load arose the senses “to be able to bear” and “to endure,” which in turn developed into 忍 and 忍耐 (“endure, be patient”). From the notion of restraining oneself so as to uphold others came further extensions such as 惻隠 (compassion), 親 (affection), and 愛 (love).²⁶

A key aspect of Katō’s methodology is his effort to identify the original—or at least the primary—meaning of a graph. Later meanings, in his view, may be semantic extensions or entirely different words for which the graph was borrowed phonetically. Katō writes:

The reason one cannot reach firm conclusions in the study of ancient China without grasping both a character’s original meaning and its derived or extended senses is that, in the classics, a graph is only occasionally used in its primary sense; far more often it appears with an extended (figurative) or borrowed meaning. If one does not know the original sense, one mistakes the extended meaning for the primary sense and ends up unable to understand the character’s structure in any coherent way.²⁷

In itself, this approach is entirely reasonable. However, many characters trace back to the earliest stages of Chinese writing, for which little or no archaeological evidence survives. Even in cases where characters have identifiable antecedents in oracle bone script or bronze inscriptions, there is often insufficient contextual information to determine their original meaning with confidence.

Katō’s main inspiration for asserting that 仁 originally related to carrying a burden is the Shì Míng—a source that, while interesting, is itself considered unreliable and dates to around 200 CE. The original form of the graph, however, could easily be a thousand years older.

Katō attempts to further support his reconstruction of the original meaning by referencing the Lùnyǔ (attributed to Kǒngzǐ 孔子 [Confucius] and his contemporaries, 475–221 BCE) and the Mèngzǐ (340–250 BCE). Katō writes:

To interpret 仁 as 忍 is in relation to oneself, and Kǒngzǐ refers to this as 克己 (to restrain one’s selfish desires).²⁸

The original text is this:

Yan [Yuan] Hui asked about Goodness (仁). The Master said, “Restraining yourself (克己) and returning to the rites (禮) constitutes Goodness (仁).²⁹

Katō gives two ways in which the semantic change of the word 仁 progressed from “the meaning of carrying a heavy load” onwards.

In the introduction he writes:

From the idea of shouldering that load arose the senses “to be able to bear” and “to endure,” which in turn developed into 忍 and 忍耐 (“endure, be patient”). From the notion of restraining oneself so as to uphold others came further extensions such as 惻隠 (compassion), 親 (affection), and 愛 (love).³⁰

In the entry for 仁 he writes:

Extending from the meaning of carrying a heavy load, it evolved into the meaning of 忍 (to endure) (as stated in the Shì Míng: 仁 is 忍), and further progressed to the meaning of “to be affectionate” or “to love”.³¹

Schuessler translates 仁 in the Lùnyǔ and in Mèngzǐ as “kind, gentle, humane”. Slingerland translates 仁 as “Goodness” and Hinton translates it as “Humanity”.³² I guess the Lùnyǔ would be the stage for which Katō suggests the meanings “compassion, affection, love”. That would mean that Katō would render this part from the Lùnyǔ as something like: “Restraining yourself (克己) [as an equivalent of “endurance”] and returning to the rites (禮) constitutes “compassion, affection, love” (仁). In other words, “compassion, affection, love” are extended meanings of “endurance” or “restraining oneself” in Katō’s view.

So perhaps the Lùnyǔ is compatible with Katō’s hypothesis. But we should not forget that he began with the pun found in the Shì Míng. Where might the author of the Shì Míng have gotten that idea? Most likely from the exceptionally famous and well-known Lùnyǔ itself. Which makes it all the more likely that the reasoning is entirely circular. Katō still needs to establish that ![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

From Mèngzǐ, Katō cites:

To interpret 親 (to be affectionate) is in relation to others, and Mèngzǐ refers to this as 不忍心 (a heart that cannot remain still). The first ancient script variant is a phono-semantic compound with the structure of “heart (心, semantic component) and the sound of 千 (a simplified character for body) (phonetic component)”, and it is a character with the same meaning as 忍.

Katō aims to link the ideas of “subdue one’s self” and “being affectionate” by way of his hypothesized original meaning of 仁 as “endure” 忍. However, it seems to me that Mèngzǐ uses 忍 with an opposite meaning. Kǒngzǐ speaks of “subdue one’s self” (without actually using the word 忍), while Mèngzǐ refers to a heart that cannot remain still—cannot endure. At present, I find it difficult to follow the logic of this progression. Given that Katō was writing for an audience composed largely of lay readers, he ought to have explained this connection more clearly.

Katō writes that in ancient seals and ancient script, the element 二 was added to ![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

However, Katō and his collaborators go beyond viewing 二 as merely an added phonetic element. Seeley et al. describe this function as a “phonetic with associated sense.” ³⁴ Many characters analyzed this way are classified by other scholars as 會意兼形聲—“semantic-phonetic compounds with associative elements”—in which the phonetic component is labeled 亦聲 (lit. “also sound”). In the case of 仁, the component “human being, person” 人 is considered 亦聲 by most scholars. As a signific, it categorizes the graph as relating to human matters, but it also functions phonetically.³⁵

What’s remarkable is that Katō identifies 二 (not 人) as the “phonetic with an associated sense.” This interpretation is elaborated in the later Kadokawa’s dictionary of the origin of Chinese characters, where Katō is listed as the lead author alongside Yamada Katsumi and Shintō Hideyuki. There, the explanation is given as follows:

(字音)ジン。「二」(じ)がこの音を表わす。「二」の音の表わす意味は、「任」(じん)(荷物の意)である。「ジ」の音が「ジン」に変わった。辭(じ)(zi)→辛(しん)(sin)、卂(しん)(sin)→迅(zin)

[The reading of 仁 is] JIN. [The reading of] 二 (JI) expresses that sound. The meaning expressed by the sound of 二 is 任 (JIN) ([which has the] meaning of luggage or a burden). The sound of JI changed into JIN. 辭 (JI)(zi) →辛(SHIN)(sin), 卂(SHIN))(sin)→迅(zin)

To unpack that a bit:

二 is the phonetic component of 仁. We hypothesize that in ancient times, 二 had a pronunciation closer to that of 仁 and conveyed the word 任, which had a similar sound. 任 refers to a burden one carries, like luggage. We believe it’s plausible that the pronunciaton of 二 /zi/ once was similar to 仁 but that this sound /zi/ changed into /zin/, based on examples such as 辭 /zi/ giving rise to 辛 /sin/, and 卂 /sin/ serving as the phonetic in 迅 /zin/, which implies that /s/ can evolve into /z/.

That /sin/ can become /zin/ is entirely plausible to me—though in this case, the authors might not have needed to bring it up. All the transcriptions and reconstructions I’ve encountered assign /s-/ as the initial for both 迅 and 卂; only Japanese renders 迅 as /jin/.

Unfortunately, I can’t make sense of the proposed scheme 辭 (JI)(zi)→辛(SHIN)(sin). Why does the arrow point from 辭 to 辛? Also, no scholars—not even Katō et al. themselves—seem to argue that 辛 is the phonetic in 辭. Most problematic is that 辛 is a pictogram, and as such necessarily precedes the compound character 辭 in development. I must be misreading the logic somehow.

Even if the proposed 辭 → 辛 derivation made sense—which it doesn’t, at least to me—it still wouldn’t constitute proof that 二 once sounded like 仁. The claim that 二 functions as a phonetic with an “associated sense” 任 strikes me as a completely unproven hypothesis.

Conclusion

In summary, this is my impression: Katō examined the entry for 仁 in the Shì Míng and the entry for 儿 in Xǔ Shèn’s Shuōwén jiězì, and from these sources developed a creative, unifying interpretation. He then turned to other ancient texts to support his view, citing passages from the Lùnyǔ and Mèngzǐ as evidence.

To me, as a non-expert, Katō’s interpretation of ![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen. p. 7, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p7-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

Additionally, it’s unclear to me why Katō’s rendering of 儿 (![[ image of early character form representing a sitting person, from Katō Jōken’s book Kanji no kigen, p. 40, entry for 仁]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/Kat%C5%8D.J%C5%8Dken-Kanji-no-kigen-p.40-proposed-early-form-of-%E4%BB%81.svg)

![[img of seal script version of 儿]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/%E5%84%BF-513f-seal-script-version-from-%E8%AA%AA%E6%96%87%E8%A7%A3%E5%AD%97.svg)

![[img of seal script version of 儿 Duanzhu rendering ]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/%E5%84%BF-513f-seal-script-version-from-%E6%AE%B5%E6%B3%A8-for-%E8%AA%AA%E6%96%87%E8%A7%A3%E5%AD%97.png.svg) ). Moreover, Katō doesn’t offer a substantive argument for the hypothesis that 二 serves as a (second) phonetic in 仁. His presentation of the quotes from the Lùnyǔ and Mèngzǐ also falls short of making a convincing case in support of his interpretation.

). Moreover, Katō doesn’t offer a substantive argument for the hypothesis that 二 serves as a (second) phonetic in 仁. His presentation of the quotes from the Lùnyǔ and Mèngzǐ also falls short of making a convincing case in support of his interpretation.

Why did Katō give his analysis of 仁 such a prominent place in his introduction? He must have felt very confident his findings would hold up to scrutiny. Yet, for now I cannot accept that his treatment of 仁 is representative of his methodology.³⁶

Notes

labeled as an oracle bone graph, which looks just like its modern form 仁, with 亻/人 as signific (MFCCD and Xiaoxuetang Database, accessed 13-06-2025). However, this early form might be a false match. Initially I thought that this graph was a recent discovery, but it’s shown in Katō (p. 39) as well, and that publication is from 1970. However, Ochiai does not list it in his 2020 overview (p.583), nor does Chi (p.632), even though the Xiaoxuetang Database has a picture of the original. (It’s 甲骨文合集 1098 on MFCCD, and 前2.19.1 合1098 賓組 on the Xiaoxuetang Database website.) Perhaps Ochiai and Chi treat it as a coincidence of 人 and 二 close together? I don’t know. Checking other standard works... Gǔ (p. 89) does show the oracle bone graph, but Lǐ et al. do not show the oracle bone graph, nor does the Hànyǔ dàzìdiǎn. Perhaps this is controversial somehow.

labeled as an oracle bone graph, which looks just like its modern form 仁, with 亻/人 as signific (MFCCD and Xiaoxuetang Database, accessed 13-06-2025). However, this early form might be a false match. Initially I thought that this graph was a recent discovery, but it’s shown in Katō (p. 39) as well, and that publication is from 1970. However, Ochiai does not list it in his 2020 overview (p.583), nor does Chi (p.632), even though the Xiaoxuetang Database has a picture of the original. (It’s 甲骨文合集 1098 on MFCCD, and 前2.19.1 合1098 賓組 on the Xiaoxuetang Database website.) Perhaps Ochiai and Chi treat it as a coincidence of 人 and 二 close together? I don’t know. Checking other standard works... Gǔ (p. 89) does show the oracle bone graph, but Lǐ et al. do not show the oracle bone graph, nor does the Hànyǔ dàzìdiǎn. Perhaps this is controversial somehow.

![[img of seal script version of 儿 Duanzhu rendering ]](https://ketmia.net/%E6%BC%A2%E5%AD%97-blog/img/%E5%84%BF-513f-seal-script-version-from-%E6%AE%B5%E6%B3%A8-for-%E8%AA%AA%E6%96%87%E8%A7%A3%E5%AD%97.png.svg) . Neither of these renderings match Katō’s graph.

. Neither of these renderings match Katō’s graph.

References

- ABCCECD ABC Chinese-English comprehensive dictionary, editor: John DeFrancis (over 197,000 entries). Pleco.

- Bottéro & Harbsmeier “The Shuowen Jiezi dictionary and the human sciences in China”, Françoise Bottéro and Christoph Harbsmeier, in Asia Major, 21 (1), 2008. (pp. 249–271) PDF.

- Chi 說文新證, 季旭昇 Chi Hsu-Sheng. 台北: 藝文印書館印行, [2004] 2014. (年9月二版).

- Duàn Yùcái 說文解字注, 段玉裁. 1815.

- Eno The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: A Teaching Translation, Robert Eno. <https://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422>, 2016.

- Gǔ 汉字源流大字典 (Hànzì yuánliú dà zìdiǎn), 谷衍奎 Gǔ Yǎnkuí. 语文出版社 Yǔwén chūbǎnshè, 2008.

- Hànyǔ dàzìdiǎn 汉语大字典 (Large character dictionary of Chinese) first edition.

- Henshall A guide to remembering Japanese characters, Kenneth G. Henshall. Tōkyō. Charles E. Tuttle Company. Rutland, Vermont & Tokyo 1990 [1988].

- Hinton Analects Confucius: Translated with commentary by David Hinton, David Hinton (translator). Counterpoint, Berkely, 2014.

EPUB ISBN 978-1-61902-686-5 - Katō 漢字の起源 (The origin of Chinese characters), 加藤常賢 Katō Jōken. 角川書店 Kadokawa shoten. Tōkyō, 1970.

- Katō et al. 角川字源辞典 (Kadokawa’s dictionary of the origin of Chinese characters) 2nd ed., 加藤常賢 Katō Jōken & 山田勝美 Yamada Katsumi & 進藤英幸 Shintō Hideyuki. 角川書店 Kadokawa shoten. Tōkyō, 1983.

- Lǐ et al. 字源 (Zìyuán), 李學勤 Lǐ Xuéqín 主编 [editor in chief]. 天津 (Tianjin): 天津古籍出版社 (Tiānjīn gǔjí chūbǎn shè) [Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House], 2012.

ISBN 9787552800692. - MFCCD 漢語多功能字庫 <https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/>

- Ochiai (2022) 漢字字形史字典【教育漢字対応版】 (Dictionary of the historical evolution of kanji forms: Edition covering all Elementary school characters), 落合淳思 Ochiai Atsushi. 東方書店 Tōhō Shoten. Tōkyō Metropolis, 2022.

- Qiú (2000) Chinese Writing 文字學概要, Qiu Xigui 裘锡圭 (Translated by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman). The society for the study of early China & The institute of east asian studies, university of California, Berkeley. Birdtrack Press. New Haven, 2000.

- Seeley et al. The complete guide to Japanese Kanji: Remembering and understanding the 2,136 standard characters, Christopher Seeley and Kenneth G. Henshall with Jiageng Fan. Tuttle. (printed in Singapore), 2016.

- Schuessler (2007) ABC Etymological dictionary of old Chinese, Axel Schuessler. University of Hawai'i Press. Honolulu, 2007.

- Shirakawa 字統 (新訂), 白川静 Shirakawa Shizuka. 平凡社, 2004.

- Slingerland CONFUCIUS Analects: With selections from traditional commentaries, Edward Slingerland (translator). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2003.

- Tāng Kějìng 说文解字:全本全注全译, translation and annotation 汤可敬 (Tāng Kějìng). 中华书局. 北京, 2018. ISBN: 978-7-101-12960-1

- Tōdō et al. 漢字源 Kanjigen (改訂第五版 Kanjigen 5th revised edition), 藤堂明保 Tōdō Akiyasu, 松本昭 Matumoto Akira, 竹田晃 Takeda Akira, 加納喜光 Kanō Yoshimitsu (eds). 学研 Gakken. 東京 Tōkyō, 2014.

- Xiaoxuetang Database <https://xiaoxue.iis.sinica.edu.tw/>

- Xǔ Shèn 說文解字, 許慎 Xǔ Shèn . [CE 121].

CC BY-SA 4.0